The World War I contributed hugely to the maturing of aircraft industry. In 1913, airplanes were still mostly viewed as a thing of entertainment with limited practical applications and frowned upon by most military planners. In 1919, nobody took the airplane lightly, for it had proven its worth during the long and hard war. Still, there was one important point left to prove: that aircraft could cross the Atlantic Ocean not just inside in a ship’s cargo hold, but also on their own. The United States Navy, Coast Guard, and Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company joined their efforts to try and prove flights between America and Europe possible.

Navy and Curtiss

Curtiss Aeroplane Company built its first floatplane, the Model E, as early as 1911. The following year it created a very successful Model F flying boat design. Throughout WWI, the company developed and produced in large numbers several other flying boat and float plane types. Such as Curtiss Model H, Curtiss Model N, and Curtiss HS.

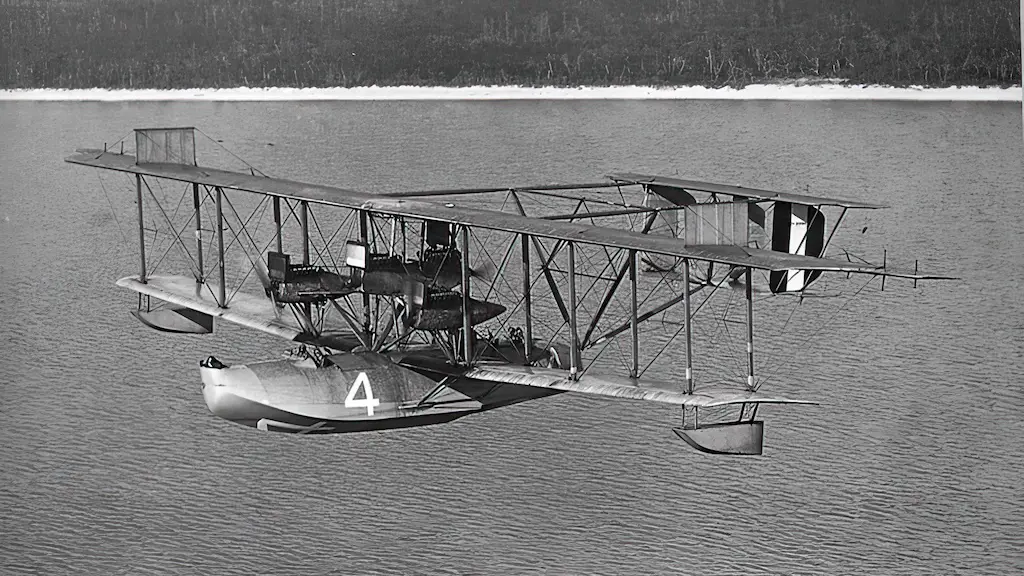

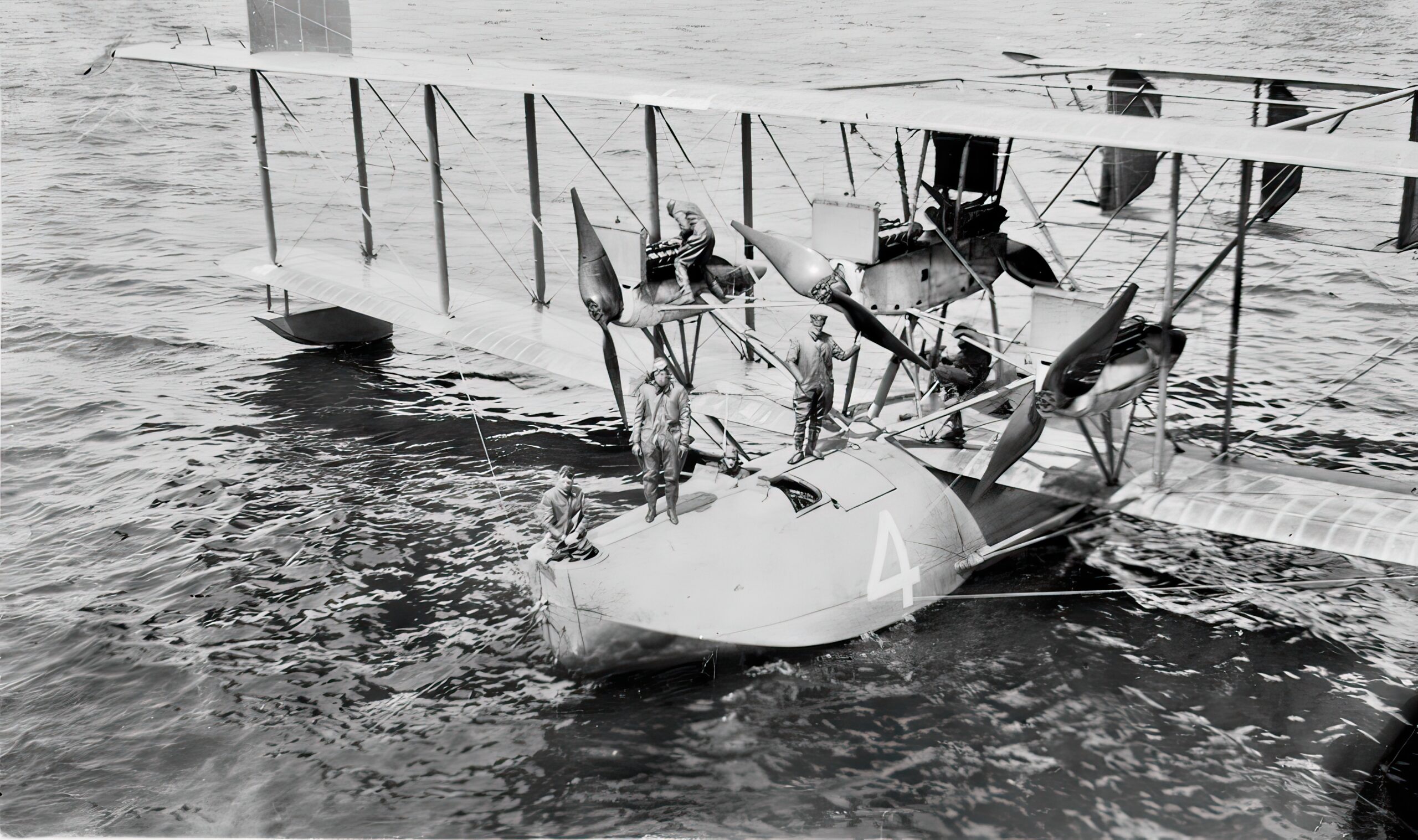

The huge experience accumulated by the company allowed it to create a series of Curtiss NC (for Navy and Curtiss) biplane flying boats. Each of these airframes had its own designation, such as NC-1, NC-2, etc. These were large aircraft for their time, over 68 ft long and a with a wingspan of 126 ft. Powered by four 400-hp Liberty L-12A water-cooled piston engines, three tractors and one pusher, they had a maximal takeoff weight of over 27,000 lb and could take enough fuel for a transatlantic flight. The NC-4 performed its maiden flight on April 30, 1919. Just over a week later it was set to write history.

Coastwise navigation

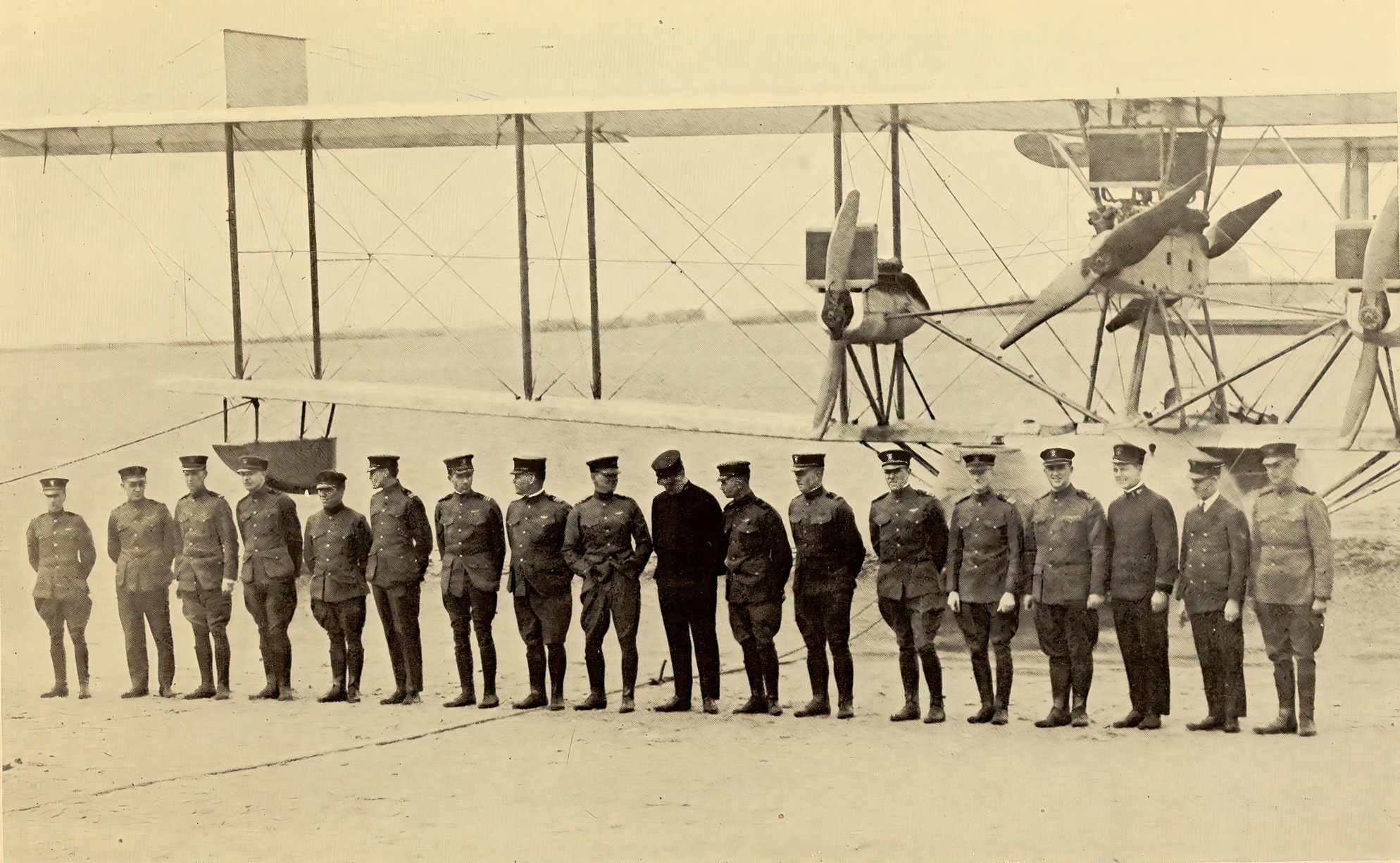

On May 8, 1919, the NC-4, accompanied by two other planes of the series, NC-1 and NC-3, set out from Naval Air Station Rockaway, New York City. Although Curtiss NC flying boats normally had a crew of five, the NC-4 had six crewmembers on the historic flight, all of them from US Navy and US Coast Guard. These were pilots Walter T. Hinton and Elmer F. Stone, flight engineers James L. Breese and Eugene S. Rhoads, radio operator Herbert C. Rodd, and commander and navigator Albert C. Read.

The expedition spent a whole week just flying along the America’s northeast coast. Their first stop was at the Chatham Naval Air Station, Massachusetts. There the NC-4 had one of its engines replaced due to failure. The next stop was in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Finally, on May 15, they arrived in Trepassey, Newfoundland.

Out in the high seas

On the evening of May 16, the NC-4, still followed by two fellow aircraft, departed Newfoundland, heading for the Azores. To provide some degree of safety for this perilous journey, the US Navy deployed 22 warships along the whole 1,380-mile-long route. They helped the aviators navigate across the ocean illuminating their way with searchlights and flares, as well as stood ready for a search and rescue operation, should one become necessary. The NC-4 spent fifteen hours and eighteen minutes on the longest leg of its historical journey before landing in the town of Horta on the Azores’ Faial Island. The other two aircraft didn’t make it across the pond, succumbing to rain, heavy clouds and thick fog. Luckily, their crews were safely recovered.

The last leg(s)

The NC-4 crew first headed for Lisbon on May 20, but mechanical problems forced them to return and spend another week on the islands, while the aircraft was under repairs. They finally reached the European mainland on May 27, after an almost ten-hour flight from the Azores to Lisbon. It thus took the NC-4 almost eleven days to get from Newfoundland to Iberia. Less than 27 hours of that time were spent in the air. The NC-4 then proceeded to Plymouth, England, via Ferrol, Spain, to add a first flight from America to England to its accomplishments. The entire trip lasted 24 days.

Sic transit gloria mundi

The British Daily Mail had announced a £10,000 prize for the first transatlantic flight back in 1913 and then renewed the offer after the war was over. However, the newspaper set a condition of making that flight in 72 consecutive hours. Hence, the NC-4’s accomplishment did not qualify for the award. But the US Navy planners never intended to win that prize in the first place.

Just two weeks after the NC-4’s arrival in Plymouth, John Alcock and Arthur Brown in a Vickers Vimy biplane accomplished the first non-stop transatlantic flight. Their sixteen-hour journey from Newfoundland to Ireland earned them the Daily Mail prize. And just like Christopher Columbus’s journey is much better known today than the exploits of Leif Erikson, Alcock and Brown’s feat has somewhat eclipsed the NC-4’s accomplishment in the collective memory.

Still, there is no way of denying that the NC-4 crew were the first men to cross the Atlantic in an airplane. Even though it took them 10 days and 22 hours. Today their legendary craft, restored in the 1960s by the Smithsonian Institution, is on display at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida.