Genesis of a Jet Pioneer

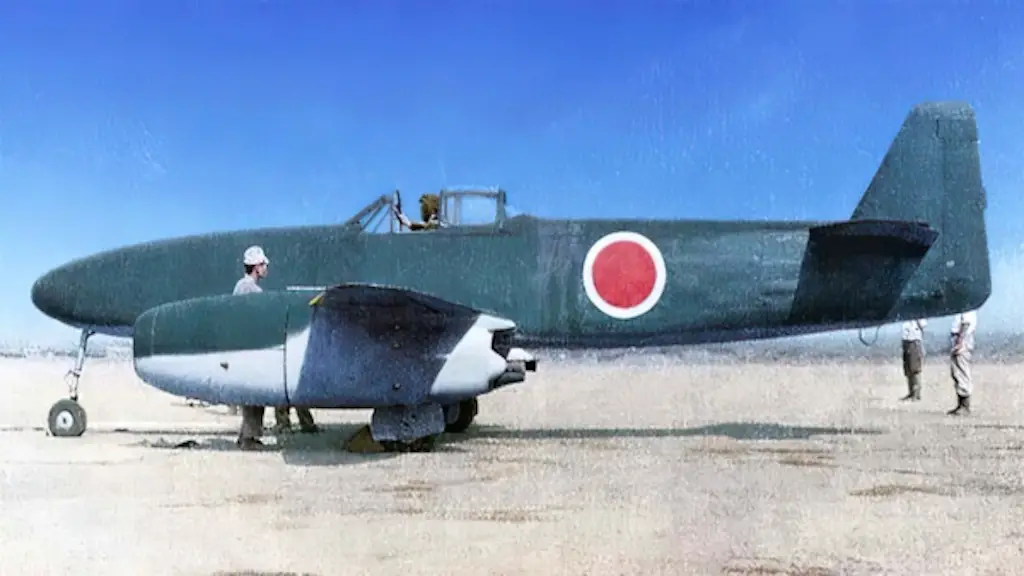

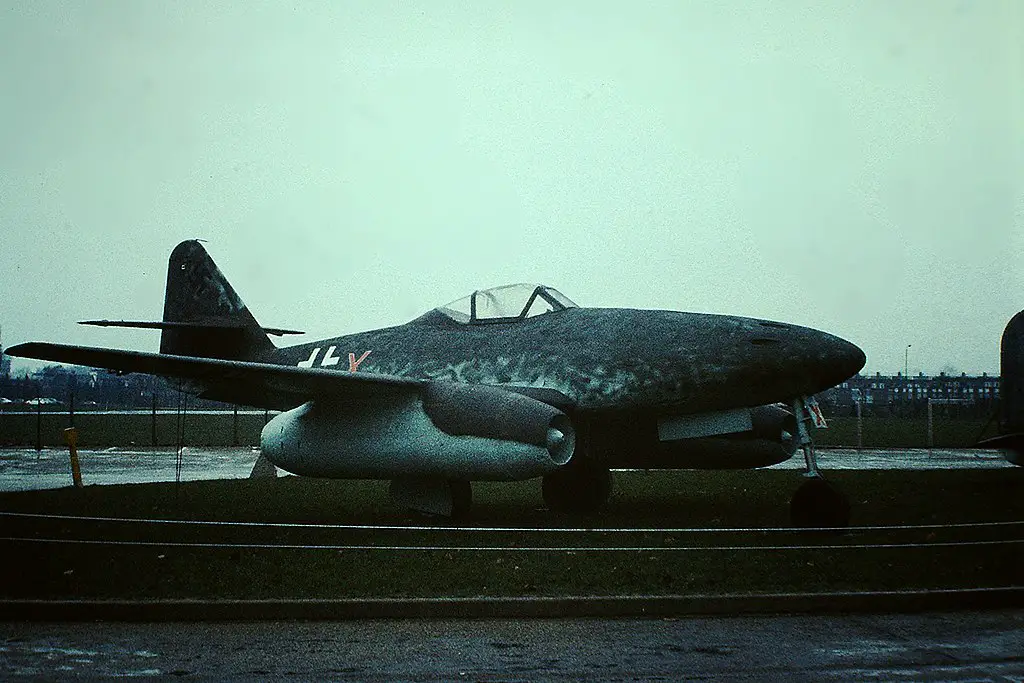

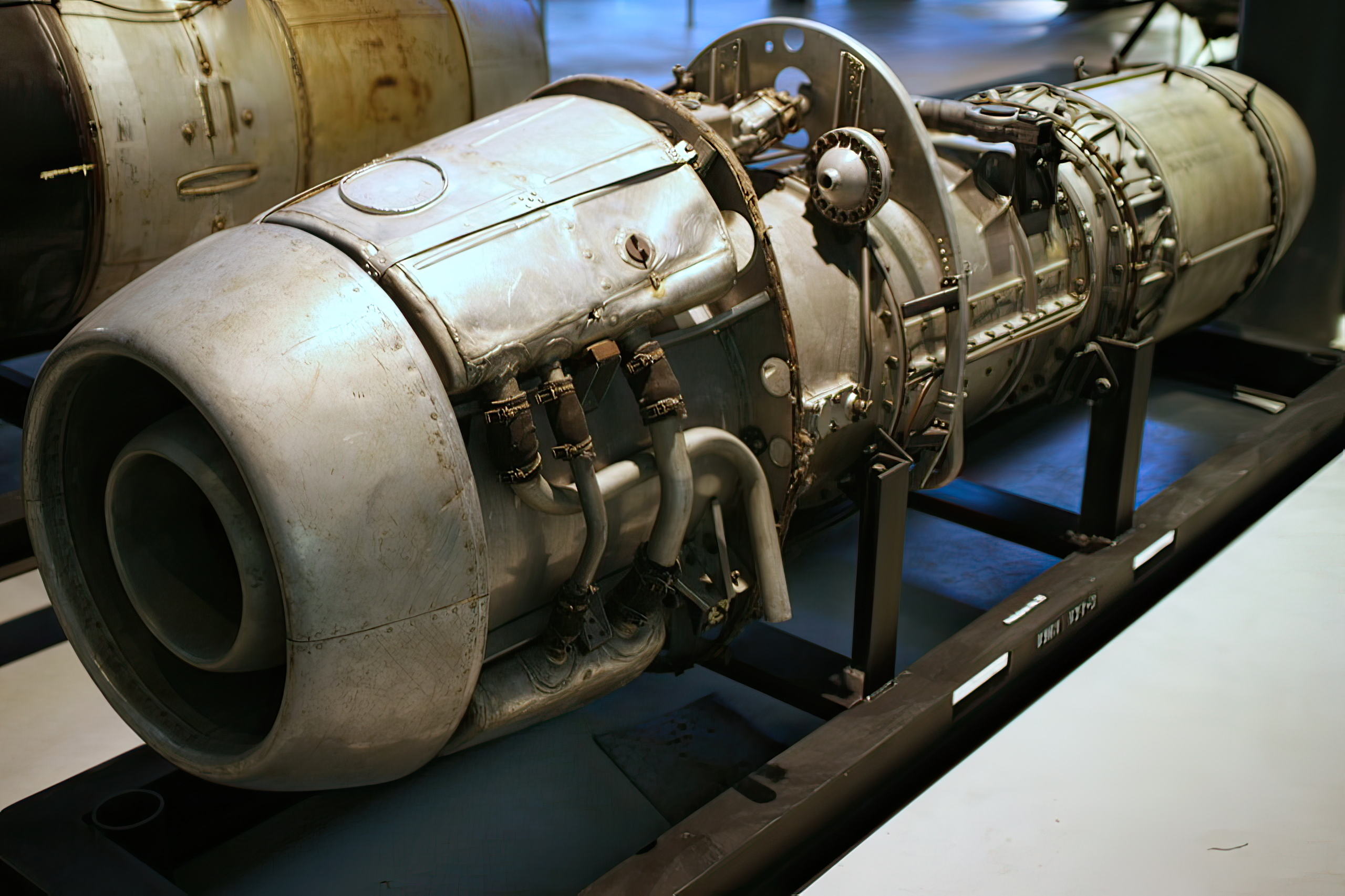

The Nakajima Kikka, meaning “Orange Blossom”, was born from the desire of Imperial Japan to rival the jet technology being developed in Europe during World War II. Conceptualized in 1944 under the influence of Germany’s trailblazing Messerschmitt Me 262, the Kikka aimed to provide Japan with a jet-powered edge. The design revolved around a unique, locally-developed Ne-20 turbojet engine, which was a smaller and simpler version of the German BMW 003 engine.

A Race Against Time

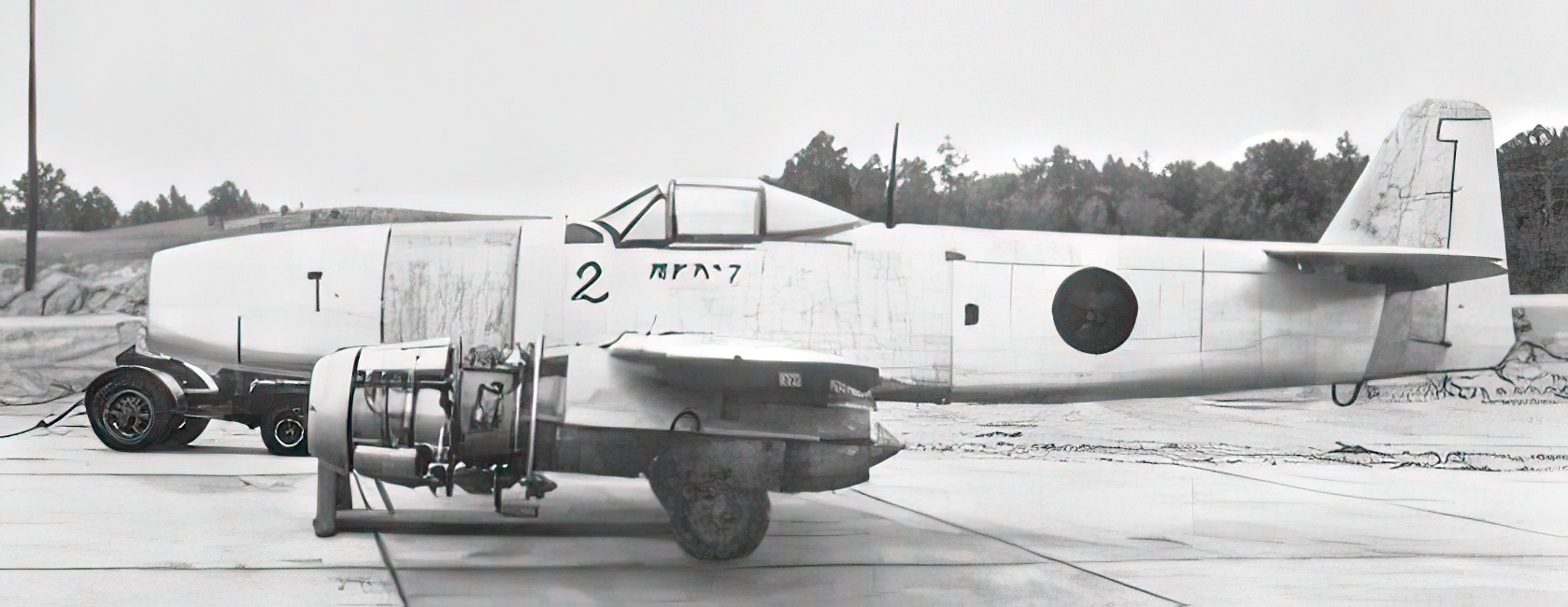

June 30, 1945, marked the beginning of the Kikka’s journey from design to reality. The maiden prototype underwent rigorous ground tests at the Nakajima factory before being dismantled and relocated to Kisarazu Naval Airfield for further trials.

On August 7, 1945, Lieutenant Commander Susumu Takaoka daringly assumed control of the Kikka’s cockpit for its inaugural flight. This event unfolded a mere day after the devastating atomic bomb assault on Hiroshima. Initial apprehensions regarding the extensive takeoff run quickly dissolved as the aircraft showcased commendable performance throughout the 20-minute test flight.

The Second Flight

In preparation for the second flight on August 11, rocket assisted take off (RATO) units were affixed to the aircraft. The pilot, wary of the rocket tubes’ alignment, but pressed for time, decided to halve the rocket’s thrust to 400 kg.

The second test flight proved challenging. The activation of the RATO on takeoff threw the aircraft onto its tail, depriving the pilot of effective tail control. As the RATO expired, the aircraft’s nose dropped, jolting the plane to a sudden halt. Struggling to abort the takeoff, the pilot grappled with the aircraft until it ran over a drainage ditch, resulting in a halt just shy of the water’s edge.

Despite the bumpy test, several more airframes were under construction, including variations such as a two-seat trainer, a reconnaissance aircraft, and a fighter equipped with two 30 mm Type 5 cannons. Designers planned for these airframes to harness the power of advanced versions of the Ne-20 engine, a promise of a boost in thrust ranging from 15% to a staggering 140%. However, Japan’s surrender brought these developments to a grinding halt.

After the War

In the aftermath of the war, a handful of incomplete airframes, including the 3rd, 4th, and 5th, found their way to the U.S. for study. Today, two remnants of the Kikka project persist at the National Air and Space Museum.

One airframe, assembled from multiple incomplete models, remains in storage at the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration and Storage Facility in Maryland. Experts speculate that workers constructed the second for load testing, and now it has a place of honor in the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar at the NASM Udvar-Hazy Center.

The Ne-20 engines also met a similar fate, with two samples shipped to the U.S. in 1946. Chrysler Corporation analyzed these engines, even managing to construct a working model from the parts and testing it for almost 12 hours. The resulting report titled “Japanese NE-20 turbo jet engine. Construction and performance” is now a highlight exhibit at the Tokyo National Science Museum.

A Nice Attempt

The Nakajima Kikka, a promising symbol of Japan’s attempt to compete in the jet age, might have met an untimely end due to the events of World War II. The Kikka’s tale is not just one of technological marvel, but also a testament to human resilience and innovation in the face of adversity.